COVID Demands an End to Homelessness

August 25/2020

As COVID-19 hits Toronto’s homeless population, those who work with and care about them are anxious on their behalf. But they are also trying to create opportunity.

Canadians may be numb to the sight of 35,000 people on the streets, but advocates have noticed the virus laying bare the public health implications of homelessness. There’s a sudden urgency to the spectre of thousands living rough — and potentially spreading the virus. It has been a rare opening to secure emergency housing for homeless people with the virus.

“COVID has impacted homeless populations, and revealed a depth of crisis that has pushed all of us to develop a sustainable system,” says Angela Robertson, executive director of the Parkdale Queen West Community Health Centre. “The kind of system that has been talked about for a number of years is now happening.

Angela Robertson, Executive Director of the Parkdale Queen West Community Health Centre. Photo courtesy of Rene Johnson/Toronto Star.

In March, Robertson began working with IHPME Asst. Prof. Dr. Andrew Boozary and Faculty of Medicine lecturer Dr. Andrew Bond (Medical Director of Inner City Health Associates) as co-leads of the Toronto Region’s COVID Homelessness Response. The initial work was to establish spaces for the homeless population to isolate and recover if they or a close contact tested positive for COVID.

Organizers were able to provide a hotel room for each person or family in Etobicoke and downtown Toronto. At the height of the outbreak, four buildings were in operation, with over 1,000 people receiving on-site access to an interdisciplinary model of health and social care that saw peer workers and community at the centre. Staff ensured that everyone had a primary care provider by the time they left the recovery centres.

“There were people in tears at having their own bed,” says Boozary, Executive Director of Population Health and Social Medicine at the University Health Network, where he works as a physician. “That’s how much we’ve failed on housing.”

“The most pressing anxiety for folks wasn’t COVID but housing,” says Robertson. “For many people, this was the first time in years they had a room of their own, washroom facilities, and a bed that was yours today and would be yours tomorrow.”

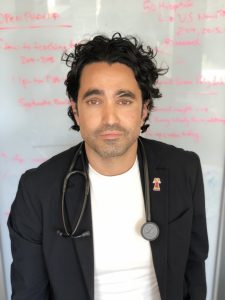

Prof. Andrew Boozary

So far, over 5,000 people experiencing homelessness in Toronto have been tested for COVID – over half the estimated population – and 1,000 have qualified for a room in a recovery center.

Although lower income and racialized people are at far higher risk, the virus has demonstrated how everyone is interconnected. Boozary says that lesson has been increasingly lost amid growing income inequality. The Toronto neighborhood of St. James Town, where Boozary grew up, is across the street from the leafy mansions of Rosedale. He recalls that nobody in Rosedale had to cross that street for any reason. The poor were invisible.

Now, with everyone affected by the shutdown, people are keenly aware of COVID’s stubborn persistence in low-income neighborhoods where people have fewer options.

“We’ve seen how anyone can get COVID if you don’t have the structural protection,” he says. “But we’ve made a choice as a society as to who’s afforded those protections. This is mired in a history of racist and discriminatory public policy. The latest COVID data show racialized people making up 83 per cent of all Toronto cases –– it is a cruel exposer of long-standing inequalities.”

With a flattening of the curve, the city’s three recovery centres are now down to one. But Boozary and Robertson fear even more families may be on the streets by the Fall, where they will be at higher risk again for COVID.

“We are staring at potentially one of the largest waves of homelessness given the unprecedented socio-economic fallout of COVID,” says Boozary. “We can continue to try for interim solutions. But to really get through this pandemic and to deliver on housing as a human right –– as well as the most effective treatment through this pandemic –– we need to convert these investments into lasting solutions.”

“We have gotten stuck in being told there is no money,” adds Robertson. “We have seen that homelessness is not an inevitable condition we need to live with just because we keep being told there is no money.”

“Given the decades of life lost to homelessness, it’s amazing that a virus is exposing how important housing is,” Boozary says. “Housing is really the soundest economic choice and the option that protects human dignity. Anything else will fall short.”